Book summary and review of Accelerate

Summary and review of ‘Accelerate’ by Nicole Forsgren PhD, Jezz Humble and Gene Kim as published on Medium

Overview

Digital transformation has changed the means by which organisations operate and define themselves. Take for example the banking industry; Dutch fintech company Bunq states that they are a software company with a banking license, rather than a bank that uses software. Along with the digital transformation comes the issue of scalability, here at Sendcloud, we are experiencing a consistent growth of users as more eCommerce businesses make the switch to digital operations.

Successful entrepreneur Hiten Shah wrote in his blog on Medium “in SaaS, you don’t win by getting there first or having the best idea. You win by continually solving the problem better. When you build a feature that’s extremely popular or successful, the competition will steal it” . This statement of Hiten applies to all software-driven companies: the faster you can develop software and the more stable you can run it, the more likely you are to be successful.

The authors of Accelerate have researched and provided what they call ‘the key capabilities that make software organisations better’.

The book reveals 24 key capabilities that have a proven impact on the performance of software delivery. These are divided into 5 categories:

- Continuous delivery

- Architecture

- Product and process

- Lean management and monitoring

- Culture

For each category, the authors then outline which 24 capabilities have a positive impact on software organisations.

Continuous delivery

1 Version control: application code as well as infrastructure configuration

2 Deployment automation

3 Continuous integration

4 Trunk-based development over long-lived feature branches

5 Test automation: reliable, easy to act on and executed frequently

6 Test data management: better test automation with adequate data

7 Shift left on security

8 Continuous delivery implementation by adapting teams, processes and architecture

Architecture

9 Loosely-coupled architecture

10 Autonomous teams with decision-making authority (empowered teams)

Product and process

11 Seek customer feedback and incorporate that in the design of products

12 Value stream: understand flow of work from business to customer

13 Working in small batches including the use of minimum viable products

14 Experiments and having authority to make changes without approval

Lean management and monitoring

15 Light weight change approval process (a heavy process is worse than having no process at all)

16 Monitoring

17 Pro-active notifications

18 Limit the amount of work in-progress

19 Visualise work

Culture

20 A generative culture of joint performance and transparency

21 Encourage learning

22 Strong collaboration between teams

23 High employee satisfaction

24 Leadership that is strong in transformation

The book is structured in line with these 5 areas and associated capabilities and consists of chapters titles as follows:

- Technical development practices

- Architecture

- Product management

- Leadership

- Culture

Within these areas, the capabilities and research are discussed, but not always in the order as above and not every capability is worked out in detail. For me this was quite confusing.

Summary and review

I read the book Accelerate in one go ― in my job, I have to complete a lot of research and this only ever happens to me when the resource has substantial information. What made this book worth my while? Accelerate provides solid research and facts about what makes successful software organisations different from the less successful, these are documented as key indicators. Finding in-depth research like this is no easy feat, making this read all the more valuable. I’ve been lucky to have had the opportunity to work for renowned Dutch organisations and I have often referred back to this book as a cornerstone for strategic scalability.

The subtitle of the book is “building and scaling high performance technology organisations”. This creates the expectation that the book describes how to build a high performing technology organisation — after all, it says “building”. The authors however do explain what to do, but not how to do it. Nevertheless, it is good to know what can make you more successful. Other books by these authors have plenty of practices you can follow. Think of The DevOps Handbook, I recommend you also read this book for more depth on specific practices, or in other words on how to do it.

The four key metrics for a software delivery organisation

The authors start by concretely outlining what defines high performance in technology organisations. It comes down to four key metrics:

- Delivery Lead Time: shorter is better

- Deployment Frequency: higher is better

- Mean Time To Restore (MTTR): shorter is better

- Change Fail Percentage: Lower Is Better

According to the authors, these metrics are good for the following reasons:

- They are team metrics, so they do not encourage sub-optimisation for one person or one team, but promote the best result for everyone; they call these ‘metrics with global outcomes’

- They measure both speed and stability; the best-performing companies combine speed and stability

The reason why they have selected these four metrics is backed up by research showing that organisations that score well on these metrics also score well in two other areas:

- Financial performance, such as turnover and profit

- Non-financial performance, such as quality and customer satisfaction

The thesis is that organisations that are good at these four metrics, are often also very successful as an organisation in general. In the book, they visualize these kinds of dependencies as follows:

Figure 1: a good software organisation influences the success of the company

Figure 1: a good software organisation influences the success of the company

I find these metrics a very strong point: what end-users or customers of a software organisation want is speed and stability. There is not much value in delivering fast when production is not stable. On the other hand you don’t want to achieve stability with controls that impact the speed of delivery. You want to have both and that is why they get to these metrics.

Now there will be readers who see the four metrics and think “doesn’t the number of production issues matter?”. Not as significantly — production issues are always present, no matter how good you are. It, therefore, makes more sense to lower the MTTR — better to have 10 issues a day that last a few seconds, rather than 1 issue lasting an hour. Therefore, MTTR is a much more valuable metric.

One aspect that I did not find a good use for was the Change Fail Percentage. Why? because from my experience I prefer using practices such as canary releasing and blue-green deployments, as they allow you to question what the definition of failure is anyway. Often, it’s more testing-in-production than failure. Moreover, when things go wrong, the MTTR becomes important again.

There is another reason why I perceive this matrix as less reliable: it does not apply in the context of a culture where mistakes are allowed to be made (as long as you learn from it). This is why I hardly use the fourth metric myself and focus on the first three. If you still want to use Change Fail Rate, measure how often a change/release fails for exactly the same reason. At least that indicates the extent to which your organisation is already learning from mistakes.

The importance of a generative culture

After the four key metrics are explained, the authors come to the point that the successful use of metrics depends heavily on the culture in an organisation. To explain different types of culture, they use Westrum’s typology for organisational cultures. They argue that in organisations based on power (pathological) or rules (bureaucratic), measuring is often a way of controlling and that people are therefore going to hide and adapt information. This is in contrast to a culture focused on joint performance (generative) where there is more transparency, a better flow of information, more learning from mistakes, etc. The four metrics would therefore be more powerful in the latter culture, the authors argue. (Westrum, 2004)

Figure 2: organisational culture influences the performance of the software organisation and of the organisation in general

Figure 2: organisational culture influences the performance of the software organisation and of the organisation in general

Later in the book they describe that ways of working in a software organisation also influence culture (i.e. the other way around). I myself have experienced this in organisations where I have worked, observing that IT departments influence the other departments with their way of working. For me, this finding in the book is therefore a confirmation of what I have seen in practice. At the end of this summary I come back to this point as it is a nice way to slowly introduce a culture change: not from management, but from the way of working in the teams.

Figure 3: software development practices influence culture

Figure 3: software development practices influence culture

Following the key metrics and explanation of their synergy with generative culture, the book moves to the more concrete part, namely the practices that are proven to lead to higher performance. These practices are examined and described in the 5 chapters listed earlier and summarised below.

Technical practices

In terms of technical practices, the research shows that Continuous Delivery (CD) has a positive impact on software delivery performance and on the performance of the entire organisation. Fortunately, the writers make the comprehensive concept of CD concrete by further explaining 5 of the 9 so-called key capabilities of CD:

- Version control

- Test automation

- Test data management

- Trunk based development

- Information security

Although these five capabilities are further developed, it remains somewhat superficial and if you want to know more about these topics, you will need to look for additional resources. The authors also did not cover all capabilities in detail, like Deployment Automation.

What is commendable is that information security has not been forgotten. In many organisations this is left by the wayside, an all too common and risky practice. I see security as part of the Non Functional Requirements (NFRs). These NFRs are important to combine speed with stability. Security is important in this, but scalability, performance, availability, and resilience are just as important. You could even argue that those NFRs are conditional for a secure environment if you define security according to the CIA triad: Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability. I’m thrilled that security is specifically noted in this book, but a section on non-functional requirements would have been more effective. Especially considering the four key metrics, for which you also have to strongly consider and implement NFRs to score well.

Architecture

In the field of architecture, the book does not cover microservices, containers, Kubernetes, or other trending technologies. They stick to the essence that a loosely coupled architecture helps you to develop software on a large scale, which in turn benefits the performance of the organisation. How you do that, you have to look for in another book (as mentioned earlier), and in this case I think it was the right decision, because this way the reader is made aware of the differences in architectural patterns, regardless of the specifics around technical implementation.

The authors’ research makes it very clear that (from architecture perspective) it doesn’t matter if you develop software yourself or whether you buy off-the-shelf software: as long as it’s loosely coupled and modular. Many engineers or engineering managers prefer to develop themselves, but this research shows that this is not relevant to the performance of the software organisation. However, it could be argued that developing software yourself is good for the motivation for the employees (see capability 23 — employee satisfaction).

Management & product development

In the areas of Management and Product Development, most IT organisations will have the biggest challenge. This is about collaborating with your client, partner, or business based on shared principles. Managing teams and making product choices is something you have to do together and that makes it hard. Many change initiatives in software-driven organisations (for example, introducing agile ways of working or DevOps practices) are driven by IT, but you get the most value when business teams align with this new way of working.

According to the authors, this way of working is about the following:

- Limit work in progress

- Make small batches

- Collect feedback from customers

- Experimentation

In another article I have once read “going fast is of no value if you don’t go in the right direction.” The practices described in the Lean Management and Lean Product Management sections help you to quickly learn and confirm whether you are heading in the right direction. In this respect, the four aforementioned practices are very important. If you focus solely on Continuous Delivery without adapting your business to these ways of working, you might be lucky and get away with it, however, it’s most likely you’ll be quickly heading in the wrong direction.

I’d like to also highlight a note from another resource — Tom and Mary Poppendieck have written a beautiful piece in their book ‘Implementing Lean Software Development: From Concept to Cash’. In their book, they compare production companies with software organisations. Work In Progress (they call it Partially Done Work) is compared to Inventory of Unfinished Goods. At production companies/factories you explicitly see this problem when you walk through the warehouse. With a non-tangible product, such as software, it is less noticeable when you have a lot of unfinished goods (in scrum: stories not done). Therefore, it is especially important in software to work in small batches with the goal of bringing them live and visualising progress. I believe that having a huge amount of unfinished goods in software teams is a common issue, where a lot of working capital has been invested without any return.

Personal development & leadership The last two topics about Personal Development and Leadership are also intertwined with stability. The key point is — you can temporarily get a lot of speed by pushing people to the edge, but for an organisation that stays fast and stable in the long term, you have to create space for individual development. The book also focuses on burnout and the positive impact of Continuous Delivery, Lean Management, and Lean Product Management on burnout.

With this in mind, I have always managed the capacity of the team well and used achievable milestones, which the team itself supports. In doing so, I have helped people to take into account space for personal development, improving non-functionals and architecture. This results in more motivated people and in the long term — faster development, because the foundation is well maintained.

This is also the point that the authors make and underpin with research: organisations that work in this way are generally more successful.

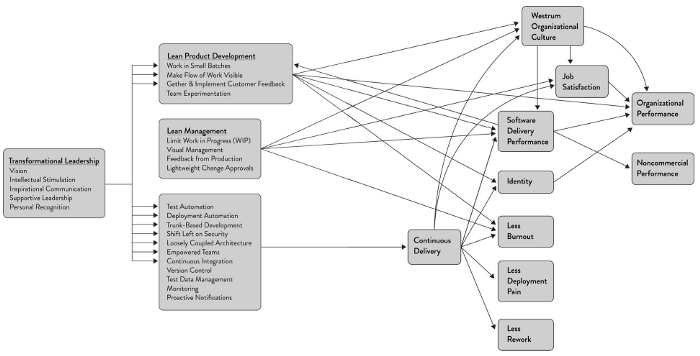

The capabilities summarised in previous sections all have a proven impact on the performance of the software organisation. Alongside this, the performance of the software organisation affects the overall organisation. In addition, during their research, the authors discovered other connections, such as the influence of practices on culture, burnout, identity, etc. You can see how these relationships intertwine in the image below.

Figure 4: an overview of all capabilities and the influence they have

Figure 4: an overview of all capabilities and the influence they have

My opinion on the book

Accelerate provides comprehensive insights. Therefore this summary cannot replace the book and I recommend you read the book yourself. The book covers really well what capabilities you need, but offers limited help on how you get from your current situation to the desired state. For example, how do I move from a tightly-coupled system to a loosely-coupled one? Or an even more complex example: how do I get to a culture required for high performance?

The book hardly answers these questions and although you know what to do after reading, you really need help and further information to figure out how to get there.

An encouraging point in this regard — according to the research, the practices also influence the culture, so, for example, if you start with small steps in CD, you are also initiating a culture change, which in turn drives the adoption of successful practices.

Figure 5: if your way of working can influence the culture, then you can start small with a big change

Figure 5: if your way of working can influence the culture, then you can start small with a big change

I can only echo the advice described in the book — start small by planting a seed today, and in two years you will have a tree.

About the authors

Dr. Nicole Forsgren is VP Research & strategy at GitHub. At the time of writing the book, she was CEO and Chief Scientist at DevOps Research & Assessment (DORA). She is known as the lead investigator of this largest DevOps study to date. She’s been a professor and performance engineer. Her publications are published in several highly regarded media.

Jez Humble is co-author of The DevOps Handbook, Lean Enterprise and Continuous Delivery (which won a Jolt award). He is currently researching the development of high performing teams as part of his company DevOps Research & Assessment (DORA). He also teaches at UC Berkeley.

Gene Kim is CTO, researcher and author of The Phoenix Project, The DevOps Handbook and The Visible Ops Handbook. Gene is founder of IT Revolution and is founder and host of the DevOps Enterprise Summit conferences.

Important note about this summary

Accelerate is a key learning resource for anyone dealing with a fast scaling organisation, therefore, this summary should not be used as a substitute for the book itself. My goal for providing this summary is to hopefully encourage you to buy the book yourself to form your own opinion. In this summary, I focus specifically on part 1 of the book. Part 2 is about the research approach and you can go through that after you have bought Accelerate yourself.